Well, I finally sat down with Ovidie’s essay La chair est triste hélas, about her four year sex strike. For those of you wondering who the heck Ovidie is, she is a French director, actress, producer, journalist, writer, and a former porn actress. While Ovidie’s short-lived porn career was over 20 years ago, and is a drop in the ocean compared to her subsequent body of work, it kind of follows her around. There’s no shame in anyone having had a porn career but there’s a feeling that certain people within the French media would happily weaponise it to try and diminish her position.

A rough translation of La chair est triste hélas would be “The flesh is sad, alas”. Chat GPT informs me that the phrase originally comes from a poem Brise marine (“Sea Breeze”) by Stéphane Mallarmé and means to convey a dissatisfaction with physical existence. In Ovidie’s case, years of bad sex with selfish (male) lovers.

Non, je ne sais pas ce que je veux parce qu’on ne m’a jamais appris à me concentrer sur mon désir. Ou plutôt disons qu’on m’a appris que mon plaisir dépendait de ma capacité à faire plaisir.

“I don’t know what I want (sexually) because I was never taught to consider my own desires. Or rather, I was taught that my pleasure depended on my ability to please others.”

(p. 60, La chair est triste, hélas, les éditions points)

Many of us can relate to this, right?

Reading La chair est triste, hélas was a cathartic experience, for both my younger and current-day self. Since girlhood, there has always been some form of fear around men. Growing up in a single parent family, my mum sent quite strong messages that they were going to mess up my life, one way or another. Boyfriends may have been banned by my mum during my teens but of course, I still absorbed all the patriarchal messages that taught me to take up minimal space and be as appealing as possible to boys and men.

One of Ovidie’s leading arguments in her essay revolves around the patriarchy assessing every woman on her fuckability, her beauty, and her sexiness. (We’ve got to be multi-hyphenates, girlies!) And, if you dare to fail at being thin and conventionally attractive, then you better have some form of talent or intelligence to fall back on, k? Because heaven forbid, we just exist at peace in this world.

Today, I’m in a long-term relationship with a loving and respectful partner, and it feels sad to have to say this, but I consider myself lucky to be with someone who understands consent.

However, there’s still a certain level of fear around men who are strangers to me — you only have to look to the Dominique Pélicot case, or the daily accounts of incest, pedophilia, rape and murder of girls and women around the world, to see why we are on the defensive.

Ovidie herself speaks of the cost of speaking about her sex strike; by flagrantly rejecting men and the possibility of motherhood for a second time, at a still fuckable age, she becomes vulnerable to insults that target her looks, her age, her choice, her attitude. Le sigh.

It was the (brief) section on friendships between straight men and women in the essay that spoke strongly to current day me.

J’aime les hommes qui ne planifient pas de me sauter, je considère que seules les relations platoniques permettent des échanges sincères et sans ambiguïté. J’aime les hommes qui, comme moi, croient en l’amitié.

“I like men who don't plan on trying to get me into bed; I believe that sincere and non-charged exchanges can only come from platonic relationships. I like men who, like me, believe in friendship.”

(p. 60, La chair est triste, hélas, les éditions points)

While I was spending my mornings with Ovidie and a coffee, I also came across this NYTimes Opinion piece by the wonderful queer writer Melissa Febos, about her 12 month sex abstinence. There were some subtle cultural differences between the two women’s experiences of celibacy, but there were also some similarities.

One difference concerned self-pleasure; I get the impression that Ovidie has always considered masturbation as a guilt-free pleasure but for Melissa, it was something she had to actively learn to enjoy, having realised that “…sex had usually included some element of performance that distanced me from my own body.”

What came across strongest, for me, in Melissa’s essay is the freedom she felt by removing herself from the game of seduction and romantic distractions. She talks of bringing more of herself into the room, which I loved, and of being able to spend more time with female friends, as well as acknowledging her people-pleasing ways when in a relationship. It reminded me that we are always learning new things about ourselves, but that we can grow with the people that we care about, instead of growing apart.

BOOK CLUB

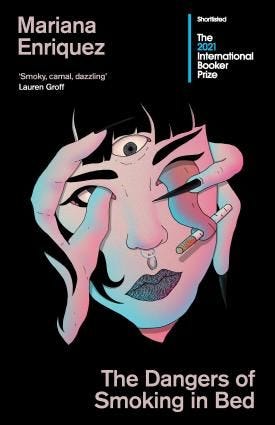

The next session will take place at Le Pavillon des Canaux on Sunday October 27th, between 4pm and 6pm, to discuss “The Dangers of Smoking in Bed” by Argentinian writer Mariana Enriquez.

As this is the month of Halloween, it felt right to embrace horror, and of course, from a feminist angle. Whether you’re coming to book club or not, this Guardian review provides a great overview of the short story collection, in case you’re on the fence about reading it.

And, in preparation for an upcoming podcast recording, I’m currently reading “Feeding the Monster: Why Horror Has A Hold On Us” by Anna Bogutskaya, who is also the host of The Final Girls UK podcast. I’m such a scaredy cat when it comes to horror, mostly watching from behind a cushion and still having vivid nightmares afterwards, but this is an interesting read that delves into fear, hunger, anxiety, and more, to explain why the horror genre “…fuels our feelings of fear, anxiety, pain, hunger and power.”

And every girl I ever talked to told me you were bad bad news

You called them crazy / God I hate the way I called them crazy too

You’re so convincing / How do you lie without flinching?

THIRTY SECOND FILM CLUB

I went on a solo cinema trip last week to see The Outrun, a film adaptation of Amy Liptrot's memoir of the same name. Saoirse Ronan plays Rona, who is about to turn 30 and struggling with an alcohol addiction that impacts her relationship, her friendships and her career.

Rona decides to go back home, to the Orkney Islands in Scotland after several hedonistic years in London. Her parents are separated, her mum found God, her dad is bipolar. We start to see some of the demons that Rona has been running from.

This new, solitary lifestyle appears to be the reset that Rona needs as she attempts to give up drinking. The film is interspersed with Scotland’s mythical stories and creatures, a feature that I really enjoyed. Not a lot happens and the film runs at just under two hours.

There are so many ways to experience addiction and mental health issues — I think the film tried as hard as it could to avoid falling into emotional clichés. Ronan’s measured performance also saved the film from becoming too sentimental. I also loved Saskia Reeves, who played her mum, and seeing how their relationship evolved as Rona started to heal.

I’ll be back soon with a new podcast episode to talk about (!)

Take care, Lou xx

A note on The FBC Paris

If you’re new here, welcome! The FBC Paris is a passion project.

Follow us on Instagram: this is where you can find out everything about our monthly book clubs.

Listen to the podcast: I chat to authors, translators, friends of the book club, and booksellers.

If there is anything you’d like to see featured in the newsletter or have something to contribute, send an email to thefbcparis@gmail.com